METAS Certification: What It Takes To Be A Master Chronometer

There are several well known international standards in watchmaking, but METAS Master Chronometer standards might be the most strict ever.

The evolution of watchmaking standards has been a very long and very slow process, which has been unfolding for as long as watchmaking has existed. This is a long time. The first spring-powered clocks were being made around five hundred years ago and as they got smaller, people started carrying them around and so the watch came to be. The first watches were by modern standards, terrible timekeepers, but eventually precision portable timekeeping became technically possible, starting with John Harrison’s marine chronometer H4 which was completed in 1759.

Precision Watchmaking And The Search For Standards

Both watches and clocks can be held to certain standards for precision. Standards for precision timekeeping were important for both scientific purposes and for practical ones, such as navigation, and eventually, during the mid-19th century, astronomical observatories began conducting tests and eventually, assigning ratings. These tests certified the accuracy of precision timepieces and corresponded to a period in time where the use of the term “chronometer” to refer to any high precision timekeeper had become generally accepted, and the observatories which provided rating services began conducting competitions as well – the Geneva Observatory, for instance, conducted chronometer competitions from 1872 to 1968. The observatory at Neuchâtel did so as well, from 1866 to 1975.

These tests and competitions were not, in general, designed to allow the certification of large numbers of mass produced watches and in Switzerland, chronometer certification for larger numbers of watches was handled by the Bureaux officiels de contrôle de la marche des montres (B.O. for short). The B.O.s were established at different locations, starting in 1877 and by the 1950s, there were testing centers in Bienne, St Imier, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Le Locle and Le Sentier, all of which were major manufacturing centers for the watch industry as well. Chronometer standards at the B.O.s were similar to today’s COSC certification; watch movements were tested for 15 days, at 3 temperatures and in five positions and from 1961 to 1973, the standard for chronometers was -1/+10 maximum deviation in rate per day.

The COSC, or Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, was established in 1973 and today provides independent third party chronometer certification. The current chronometer standard, ISO 3159, appeared in its first version in 1976 and was the first true international standard for watch precision; the standard was last updated in 2009.

ISO, the International Organization For Standardization, also publishes standards for water resistant watches, diver’s watches (with a subcategory for watches suitable for saturation diving) and antimagnetic watches. These three, along with the chronometer certification, were for many years the basic standards on which the watch industry in Switzerland and for that matter, around the world, took as the basis for manufacturing standards. These co-existed along with individual manufacturer’s internal standards for precision and performance, which can sometimes exceed the COSC standard (the Rolex Superlative Chronometer standard, in force since 2015, includes COSC certification, and also a final internal rating done by Rolex with a standard of -2/+2 seconds per day). Other independent standards exist as well albeit on a smaller scale, including the Poinçon de Genève/Timelab certification, the Qualité Fleurier certification and the Chronofiable certification. The latest, and in some respects the most stringent, is the Master Chronometer certification, which is administered by the Swiss Federal Institute For Metrology, and currently used by Tudor and Omega.

There has been a debate going on for as long as I’ve been interested in watches, on whether or not COSC chronometer certification is really meaningful anymore. How much value added it represents depends a lot of your personal tastes and priorities as a collector (if you are heavily invested in hand-skeletonized pocket watches from the mid-20th century, you probably don’t have high precision as a major priority). I think it’s worth pointing out, though, that to this day only about 6 per cent of all Swiss mechanical watch production are COSC certified chronometers, which makes it a mark of distinction even without any other considerations.

The Master Chronometer METAS Standard

However, the biggest leap forward in a watch standard from an independent third party body took place in 2015. This was the year that Omega introduced Master Chronometer certification, in partnership with METAS, the Swiss Federal Institute Of Metrology. Master Chronometer certification has come to be called “METAS certification” by metonym, but Master Chronometer is the actual name; METAS is the certifying entity. The announcement of the certification had been preceded, in 2013, by the introduction of the Omega Aqua Terra > 15,000 Gauss.

The Master Chronometer standard requires COSC certification as its basis, which means that any Master Chronometer watch has to have a COSC certified movement inside. However, Master Chronometer certification includes other addition criteria.

First of all, a Master Chronometer must run to better precision than the COSC standard; the Master Chronometer standard is 0/+5 seconds per day, compared to -4/+6 for COSC ISO 3159 certification. This is one of those areas where you can really see the advantages modern watchmakers have over previous generations – modern high precision manufacturing, computer controlled milling machines, and highly rationalized parts inventories have all made it possible to produce mechanical watches in quantities and to levels of accuracy unprecedented in the industry.

Second, Master Chronometer watches are tested fully cased. This is necessary thanks to a couple of the Master Chronometer test requirements, including those for resistance to magnetism, as well as a required pressure test. (ISO 3159 says that either a movement alone or a “watch head” – a cased watch without bracelet or strap – can be submitted; COSC can test both but the standard leaves the choice up to the manufacturer.

Third, Master Chronometer certification evaluates power reserve, in order to ensure that the manufacturer’s claimed power reserve corresponds to actual performance.

And lastly – and this is the aspect of Master Chronometer certification which is the most talked about – a Master Chronometer must be able to withstand magnetic fields of at least 15,000 gauss, without stopping (the standard specifies a field of 1.5 tesla, which equals 15,000 gauss). The standard says that the watch must be exposed twice for 30 seconds each time, with the magnetic field lines aligned vertically and then horizontally across the watch case. Interestingly enough, and this is something I didn’t realize until I read the actual standard (which you can download right from METAS although fair warning, it’s not exactly a page turner) a watch subjected to the magnetism test is required to not stop – it’s not tested for any additional rate changes and the watch has to be demagnetized right after the test.

Who Can Submit Watches For Master Chronometer Certification?

If Master Chronometer certification offers so much additional reassurance in terms of performance, you might be wondering why more brands haven’t adopted it. One reason is that it’s basically impossible to make a watch that meets the Master Chronometer criteria unless you use a silicon balance spring or some other amagnetic material (like carbon fiber) and you also have to use amagnetic materials in the escapement as well, especially the lever and escape wheel. The original patent for silicon balance springs, which were pioneered by a consortium consisting of CSEM, Swatch Group, Patek Philippe, Rolex, and Ulysse Nardin, did not expire until November of 2022, and for brands not already using them, switching over represents re-tooling production and altering supply chains. Unless a brand is part of a group with a large industrial base, the economies of scale necessary to make such a switch worthwhile are not there – and you can still get excellent performance out of non-silicon components.

The standard also restricts Master Chronometer certification to “Swiss Made” watches, so we won’t be seeing it given to watches made in Germany or Japan – probably ever; so it represents a competitive edge not just for Tudor and Omega, but for Swiss watchmaking in general as well. (COSC certification is restricted to “Swiss Made” watches as well). Both Seiko and Citizen have considerable internal expertise in silicon fabrication, and the industrial base necessary to produce silicon mechanical watch components, although in both cases, technology initiatives in precision timekeeping are largely in the quartz oscillator domain, and, in the case of Seiko, in Spring Drive technology.

METAS Master Chronometer Certification: What’s In It For You?

Almost immediately after Omega announced its adoption of the Master Chronometer certification and testing, questions arose as to whether or not such tests weren’t overkill, largely on the argument that you are not liable to run into anything approaching a 1.5 tesla magnetic field outside an MRI machine or a particle accelerator like the Large Hadron Collider, whose electromagnets generate fields of up to 8.3 tesla. If you would like to experiment on your own watch, which I hasten to add you do at your own risk, you can buy commercially available permanent magnets for things like magnet fishing (I found one after less than 30 seconds which has a surface field strength of 12,600 gauss, or 1.26 tesla).

However, magnetic fields from things like consumer electronics and permanent magnets, found in everything from refrigerator door seals to clasps on purses and cell phone cases, are more common. One very common use of permanent magnets is in laptop computers; another is in mobile phones; the iPhone, for instance, has an internal permanent magnet used to align the phone for wireless charging.

These magnets aren’t nearly strong enough to actually stop a watch, and magnetic field strength falls off very rapidly over very short distances so as a rule such fields may not have any particularly noticeable immediate effect, although they can if you happen to put your watch directly adjacent to one. I happened to put my 1990s-era Speedmaster down on a magnetic phone case clasp many years ago and it instantly began to gain 20 seconds per hour, and adverse effects of magnetism on watches are common enough that every watch workshop has a demagnetizer, which is getting a workout; they are routinely used during servicing. Aside from more subtle direct effects of magnetism on rate, exposure to weak magnetic fields over time can actually change the temperature compensation properties of Nivarox-type balance springs, which are the most widely used in the industry (silicon balance springs are hard on their heels, though).

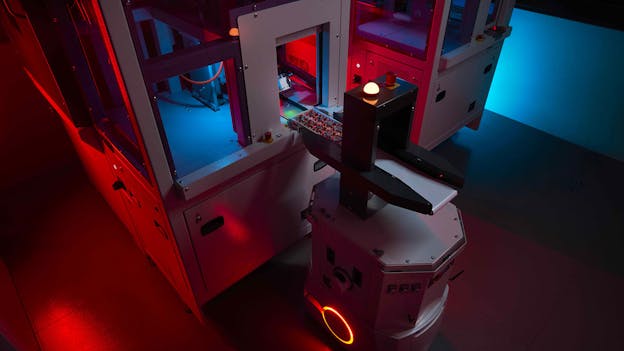

METAS Master Chronometer certification also offers a third party guarantee of performance in power reserve, case pressure integrity (although Master Chronometer certification does not require testing to the ISO 6425, the diver’s watch standard). The standard is administered by METAS which conducts periodic spot checks at both Omega and Tudor, the two brands currently using the standard; the METAS testing room is a separate room at the factories, which is accessible only to the METAS inspectors.

Omega’s mechanical watch production is almost entirely Master Chronometer certified at this point and Tudor, having just opened its new factory in Le Locle in 2023, is moving to use Master Chronometer certification more widely as well. Master Chronometer certification is certainly not the only route to high performance and precision in mechanical watchmaking but in that domain, it remains a uniquely comprehensive – and uniquely Swiss – objective standard for excellence in modern mechanical horology.